It’s been shown many times, again, with a lot of different studies around quantifying load, that if everything is always high then you never really hit your peaks because there’s a form of monotony Everyone self-paces and it’s not possible to run a marathon at a 100 meters sprint pace. So there has to be some form of modifying intensity. If volume is high and we’re spending four hours on court it’s not possible to do the some of the hardest drills, four hours continuously. It’s also not possible to have some of your hardest days five days a week or five days in a row. So, I think prospectively planning out days with different lows, whether it be a high day, a medium, day or a low day is important.

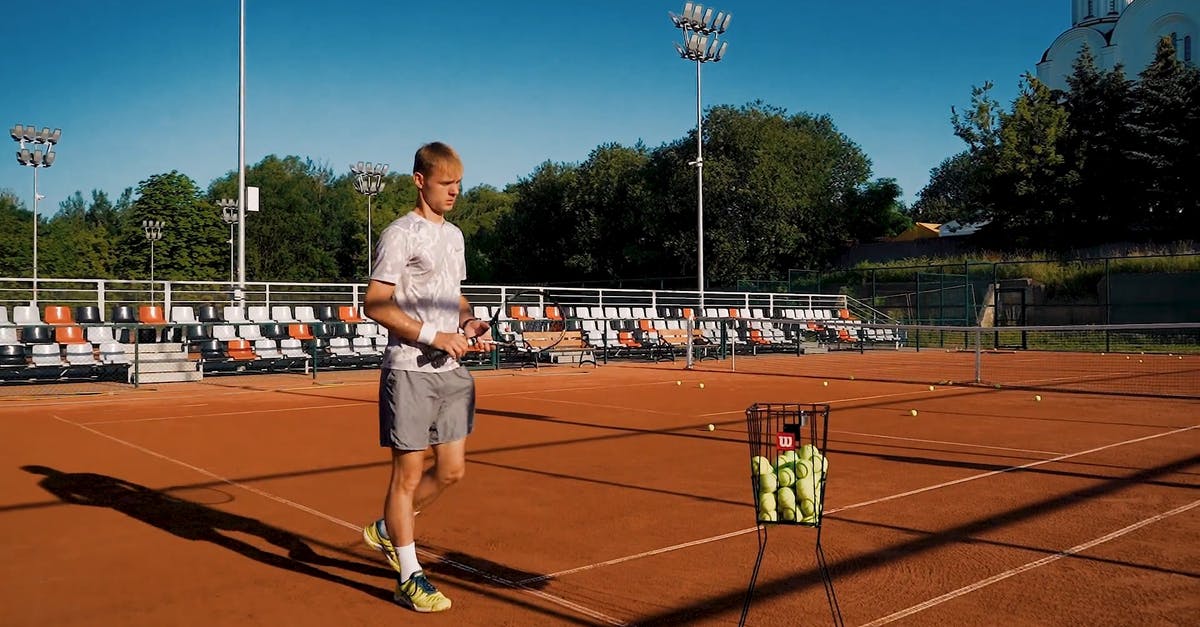

So how do I quantify drills?

There is a lot of value in terms of understanding as to what your low drills, low intensity and what are your medium intensity drills, and what are your high intensity drills. Volume is going to have a strong interaction with that. Your low intensity drills you can have a higher volume of that. Medium, you’re going to need to bring that down a little bit and then your high intensity drill you definitely need to have a low volume.

The second part is twofold, where you look at how does that map out across the week. You’d like to be prospectively planning your week out to try and work towards a bigger goal in terms of how you’re trying to develop that player, whether it be technical, tactical, physical or mental.

You need to be asking yourself: “Am I simply just walking onto the court or into the gym doing this today because I see that on the court and it’s just sort of spur of the moment and just planning session to session or day to day, or am I planning my weeks out specifically with a goal in mind of trying to develop certain qualities within that player over time?”.

If you’re doing the latter, then there is definitely a space to think:

– What days are my high days where I’m really going to push the player from a technical, tactical, physical or mental perspective

– What are my medium days?

– What are my low days?

When you are quantifying lows it relates more with their previous injury history or potential injury risk. If you have a player with a previous wrist injury, potentially a lot of low forehand work might be a little bit of a red flag, and that’s something to be aware of. Another example of previous injury history could be elbow and you’d have to be conscious of the serve. Shoulder would be another example regarding the serve. If, the player has had previous knee injury, then some of your wider forehand or backhand work, depending on which leg it is and potentially serve as well with landing on that front leg. So, all of these are important factors to consider.

What could be changed based on the statistics now available?

Historically tennis is a sport which is high volume, high density with lots and lots of repetitions. There’s a lot of space, a lot of justification, a lot of reason for that. But there’s also a large amount of space now armed with the rally length information for us to say potentially more emphasis could be placed on shorter, sharper drills that are focusing on some of the more percentage-based very important parts of tennis.

So, working on the serve, working on the return, working on the serve +1 or return +1 are we doing that safely?

All of these are low volume. So, it makes sense to quantify a lot of the drills and understand where they sit and then where do they sit across a week and how you best place your players to get the most out of that training by having fluctuations. So, you have some peaks and troughs, you have some mountains, you have some valleys. If everything is always the same, it’s very difficult to get a change or potentially the changes are suboptimal if you’re doing that.

Let’s get low practical

Question: Depending on where you are in the season and what you are practicing towards. If you, e.g. have just done a drill that was physically very demanding and high intensity would it then be preferably to follow that physically very demanding drill, by having a low intensity physical drill, but then high demanding on a technical aspect could be practicing the dropshot or whatever small technical detail.

It depends on the players training age technical proficiency. So, if you’ve got somebody with a high training age and someone who is technically proficient in the area, that’s probably okay because the player will have a strong base to fall back on. Further they’re probably less likely to get injured from that, but they’re also less likely to experience repeated failure because they’re fatigued and you’re just pushing the boundaries out on something which they’re already quite good on, but they could potentially get better as well, under fatigue.

Getting better under fatigue is something other sports have done a lot of work on. They create worst case scenarios or practice technical drills while under fatigue because that’s ultimately where a lot of the success or failure falls upon is can you execute something which normally you would be able to do, but when you almost have to and sometimes that can be mental acuity or technical acuity. It can be tactical. It can be a combination of all of these things.

If you take the opposite example. If you have a young tennis player, they’re not physically mature yet and they don’t have a full repertoire from a technical perspective. If you then place them in that fatigued environment, you’re potentially setting them up for failure. That can maybe have some impact from a psychological perspective. Further it can impact the development on the specific shot that you’re trying to have them execute. So, it depends on if you’re talking about somebody who’s has a higher level, then it’s a really good way of developing them in a fatigued state. For younger players, take a step back, look at it from a bigger picture and ask yourself: “What’s the objective here? And is that player ready for that kind of exposure?

…and if we take a look more globally on the weekly planning of a tennis player?

Q: Would it then make sense to have e.g. a Wednesday afternoon session that in general is relatively low intensity?

Yeah, definitely. Having either a Wednesday or a Thursday be a low load day or a half half day. There’s a lot of evidence and a lot of logical thought processes that support that. It’s very difficult to go hard and heavy every day. It definitely makes sense breaking up the week, whether it be a five-day training week or a six-day training week into two chunks. You might then have two-three days on hard, followed by half day lower and then by three days on.

It’s very difficult to look at training weeks from a Monday to Sunday or Monday to Saturday perspective. From an individual perspective and players who are competing the tour it makes more sense to look at it from a number of training days. So, you may not have a week. The week may not go from Monday to Sunday. Your training week might start on a Tuesday, and you may have all the way through till maybe the following Wednesday. So then at which point you have eight days of training. How are you going to structure those eight days? So, you have a match and then instead you are counting match minus one, minus two, minus three.

This way of approaching planning is very typical in other sports, but in the academy environments, the Monday to Sunday, the typical calendar week makes sense because that’s how a lot of it operates. On a more individual level, tennis doesn’t operate on a Monday to Sunday basis. You can be out on a Tuesday, you can be out on a Friday, you can be out whenever and starting a period of a short training exposure. So, looking at it from training day one up to training day six, or breaking up the days in terms of two-three days on with a low day, I think definitely makes a lot of sense.